Venice, often known as “The Floating City,” is an architectural marvel and a testament to ingenuity and resilience. Home to lavish palaces, intricate canals, and storied streets, Venice has seen the rise and fall of empires and survived wars and floods. You can also trace the city’s indelible mark on global trade, art, and culture. This blog post will discuss how an amalgamation of small islands became one of Earth’s most influential and prosperous cities.

Founded in the 5th century CE and spread over 118 small islands in the marshy Venetian Lagoon along the Adriatic Sea in northeast Italy, Venice emerged as a prominent maritime republic during the Middle Ages. The city became a significant financial and merchant power during the Crusades, benefitting from the shifting trade routes. However, the history of Venice reached its apex in the 14th century.

During this period, Venice was at the center of a trade network that extended across much of Eurasia. Hence, it became an art and cultural center during the Italian Renaissance. A pivotal moment in Venice’s history was the Fourth Crusade’s sack of Constantinople in 1204, which bolstered Venetian dominance over sea routes. However, by the late 15th century, its power began to decline due to the discovery of new trade routes around Africa that bypassed the Mediterranean. After a short period of Spanish dominance, Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Venice in 1797, ending its centuries-long independence.

Early History of Venice

The origins of Venice and the Venetian Lagoon trace back to the Paleoveneti people who settled in this region between 1000 and 500 BCE. Archeological findings suggest their presence through artifacts and inscriptions found in the area. In the 5th century CE, as the Western Roman Empire declined, inhabitants from the mainland sought refuge from invading barbarians in the marshy lagoon islands. They found a natural fortress against the incursions in these difficult-to-access islands.

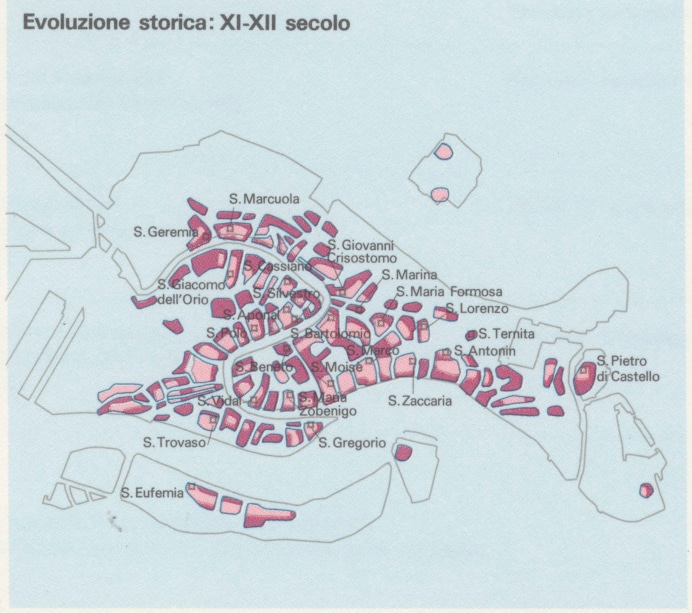

During the early Middle Ages, these lagoon communities consolidated power, gradually forming the Republic of Venice. The process of land reclamation through the construction of canals and buildings on wooden piles began around 421 CE, with the city’s founding, according to tradition, on March 25th (the feast of St. Mark). By this time, fishermen and salt workers had already developed small settlements on some islands that form the modern archipelago.

Venice’s geographic position at the northern end of the Adriatic Sea gave it significant strategic importance for Byzantine-Italian relations and in exploiting maritime trade routes to the East. Strategically aligned with Constantinople after 726 CE, thanks to successful defiance against the Lombards, it grew in influence and territorial control incrementally.

By the conclusion of the first millennium, Venice demonstrated a robust self-governance system revolving around an elected doge (duke). The Rialto area became an important center for commerce, reflecting Venice’s growing importance as a maritime power. The Venetian Lagoon functioned as an important hub for trade and shipbuilding activity that would hold a substantial role throughout Venice’s later history as a maritime republic during medieval times.

The Republic of Venice

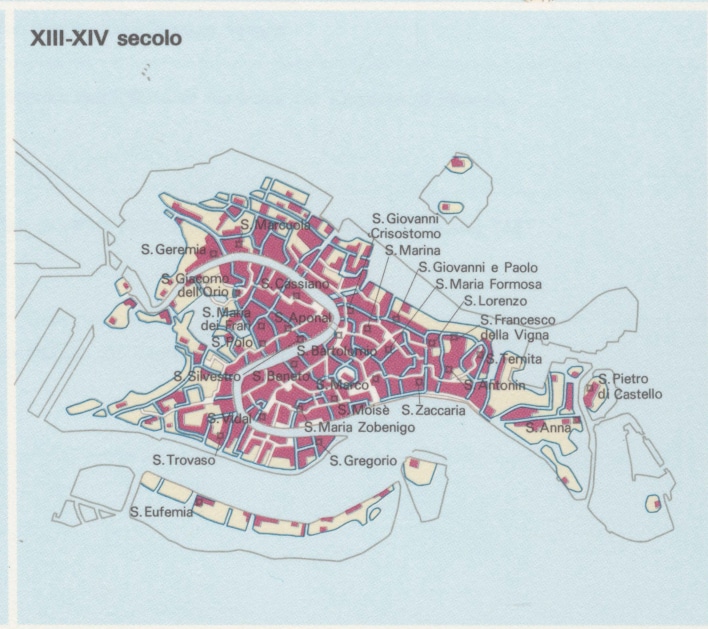

The Republic of Venice emerged as an independent city-state in the 7th century AD. Over the years, Venice gradually expanded its dominion over a number of islands and coastal areas around the Adriatic Sea – known as the Stato da Mar (State of the Sea), which included territories such as Istria, Dalmatia, and even parts of Greece and Cyprus.

During its peak era (13th – 15th century), the Republic of Venice wielded immense political and economic power thanks to its trade links with regions such as Byzantium and Asia. These connections enabled it to engage in exchanges of goods, ideas, and culture. One significant event took place in 1204 when Venice played a crucial role in the Fourth Crusade; this led to its temporary rule over one-quarter of the Eastern Roman Empire – including parts of Constantinople itself.

A sophisticated political system characterized the Republic’s governance structure. The Doge was elected for life from Venetian patricians by The Great Council. This entity wielded legislative authority while smaller advisory councils carried out day-to-day executive control. Additionally, a unique judicial system was led by magistrates who oversaw legal matters.

However, the Republic’s fortunes declined after 1500 due to several factors, such as Ottoman expansion into territories previously controlled by Venice, maritime competition from Spain and Portugal as they explored new trade routes via the Atlantic, and financial losses fueled by military conflicts against neighboring states. In 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte’s forces invaded Venice during his Italian campaign. This event marked the end of the Venetian Republic as it subsequently ceded its territories to the Holy Roman Empire.

Venice after the Napoleonic Wars

In 1797, Venice experienced a major turning point when the Republic of Venice surrendered to Napoleon Bonaparte’s French army during the First Coalition. This marked the end of over a thousand years of independence for the maritime city-state. The treaty, signed in Campoformio on October 17, 1797, dissolved the Venetian Republic. Its territories were divided between Austria and France.

Under Austrian rule, from 1797 to 1805, the mainland Venetian territory was reorganized into administrative districts under the Holy Roman Empire. Suppressing monasteries and redistributing church property significantly altered Venice’s economic landscape. 1805, following Napoleon’s triumph at the Battle of Austerlitz, Venice became part of the Kingdom of Italy under French control. Napoleon initiated a series of public works projects to modernize Venice’s urban infrastructure during this time.

The Congress of Vienna in 1815 led to another significant shift in power in Venice. Its territories were again returned to Austria under the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, which lasted from 1815 until 1866. Under Austrian rule, Venice underwent further infrastructural development. This development included the construction of railways connecting it to other parts of Italy and Europe. However, this period caused a lot of political unrest among Venetians who demanded greater autonomy or unification with an independent Italy.

Finally, in 1866, after a victorious Third War of Italian Independence against Austria, Venice was annexed into the newly formed Kingdom of Italy under King Victor Emmanuel II. This marked Venice’s final incorporation into what would later become modern-day Italy.

History of Venice after Italian Unification

The city’s incorporation into Italy led to a period of both upheaval and modernization. Venice underwent significant urban and infrastructural transformations during the final decades of the 19th century. The construction of the railway bridge connecting Venice to the mainland in 1846 was instrumental in integrating the city into Italy’s transport network. Completing the Stazione Santa Lucia in 1861 also positioned Venice in the national rail system.

The 20th century marked a time of rapid transformation and challenges for Venice. The onset of World War I saw Venice become a target due to its strategic location, but it escaped significant damage. However, World War II brought more substantial peril; although parts of its historic infrastructure suffered injury, tireless efforts allowed for swift post-war restoration. The economic revival post-1945 induced tourism growth, becoming dominant in the city’s economy. Amidst modernization, from 27 November to 4 December 1966, Venice endured the disastrous “Grande Acqua Alta,” a record-breaking flood. This flood immersed much of the city underwater and prompted international calls for preservation.

Venice faced threats from rising sea levels and subsidence throughout the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st. These threats continue to pose severe risks to its integrity. In response, numerous efforts were aimed at safeguarding Venice against high water occurrences, most notably MOSE (Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico).

Venice entered the 21st century grappling with complex challenges. The city needed to find ways to manage its status as a UNESCO World Heritage site while accommodating commercial activities.

The issue of mass tourism has escalated to a point where it threatens the integrity of the city’s infrastructure. It also poses problems for its inhabitants’ quality of life. In response, legislation to manage tourist flow was enacted, as evidenced by the day-tripper tax introduced in 2020. This tax aims to mitigate overcrowding by requiring day visitors to pay an access fee. The city council continues to debate further measures, such as instituting visitor quotas or rerouting large cruise ships which had been traditionally allowed to dock within proximity of the city’s key landmarks but have been re-routed outside of the lagoon in 2021, following a government decree due to concerns over safety and environmental harm.

Leave a Reply

View Comments