If you’ve ever looked at Turin’s skyline and wondered why there’s a building that looks like it’s trying to touch the clouds, that’s the Mole Antonelliana. Originally meant to be a synagogue, it became one of the city’s most iconic landmarks—and home to one of the coolest cinema museums in the world.

At 167.5 meters, it’s impossible to miss, and whether you’re interested in architecture or history or just want an incredible view, this place delivers. Plus, there’s an elevator that shoots you straight up through the middle of the building. It’s part history lesson, part engineering marvel, and part “hold on to your stomach” experience. Let’s get into why this place is worth a visit.

Mole Antonelliana: Historical Background

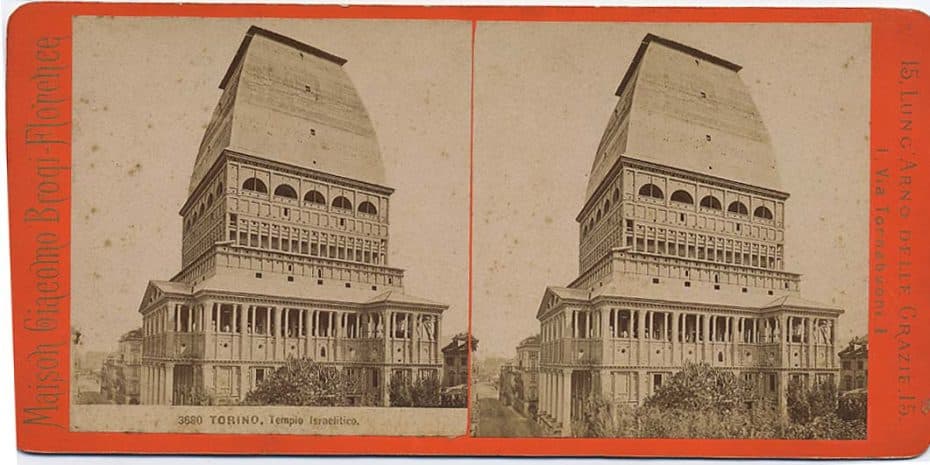

In 1863, Torino was still adjusting to its role as the first capital of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy (1861–1865). It was a time of transformation, and the city’s growing Jewish community, which had been granted full civil rights just a few years earlier, sought to build a grand synagogue as a statement of their new status. Before this, Jewish religious life in Torino centered around smaller, less prominent places of worship, as restrictions under previous regimes had limited their ability to construct large religious buildings.

Alessandro Antonelli and His Vision

To bring their vision to life, the community commissioned Alessandro Antonelli, an architect already known for his unconventional designs and structural ambitions. Antonelli was not part of the Jewish community but was a prominent Italian architect famous for his ambitious and often structurally daring projects. Before the Mole Antonelliana, his most notable works included:

- The Basilica of San Gaudenzio (Novara, 1832-1888) – Featuring a towering 121-meter dome, this church was Antonelli’s first experiment with extreme height in masonry structures, laying the groundwork for his later work on the Mole.

- Casa Bossi (Novara, 1857-1864) – A neoclassical residential palace showcasing his attention to symmetry and monumental scale.

- The unfinished Tower of Villata – An ambitious project that was ultimately abandoned but reflected his fascination with verticality.

The Ever-Changing Plans

The original plan for the synagogue was far more modest—a relatively standard structure with a height of about 47 meters—but Antonelli, obsessed with pushing limits, kept revising the design to make it taller. While the Jewish community had initially allocated around 500,000 lire (a significant sum) for the project, Antonelli’s continuous modifications and structural reinforcements caused costs to spiral beyond 1.5 million lire by 1869. By then, the structure had already reached 70 meters, consuming far more resources than originally expected.

Abandonment and City Takeover

Faced with financial strain and an increasingly impractical project, the Jewish community abandoned it in 1873, selling the unfinished structure to the city of Turin. At that point, a substantial portion of the base and lower sections of the dome had been built, but it still lacked its now-famous spire.

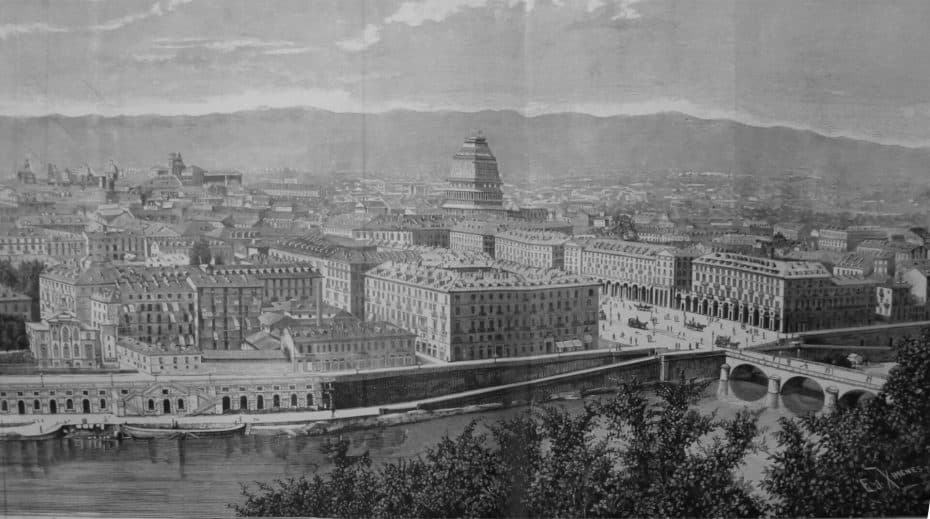

After acquiring the structure, the city considered several functions for it. Some proposals included a scientific or cultural institution, but Antonelli was granted full freedom to complete his vision. By 1889, he had extended the Mole to its final height of 167.5 meters, making it the tallest brick building in the world at the time. The name “Mole” (meaning a massive construction) reflected its imposing scale.

Notably, the fact that the Mole Antonelliana was never used as a synagogue may have contributed to its survival during the fascist regime and World War II. Many Jewish places of worship and businesses across Italy were either destroyed or repurposed during Mussolini’s rule, particularly after the introduction of anti-Semitic racial laws in 1938. Torino’s main synagogue, completed in 1884 at Piazzetta Primo Levi, was heavily damaged during the war but later restored. Had the Mole remained a synagogue, it might have faced a similar fate, making its eventual role as a cultural institution all the more significant.

Cost and Adjusted Value

Despite its completion, the Mole remained largely underutilized for over a century. It hosted temporary exhibitions, stored civic documents, and was even considered for conversion into a science museum before finding its true vocation in 2000 as the National Cinema Museum. The project’s total cost, including its final restorations, exceeded 2 million lire—an astronomical sum for the era. Adjusted for inflation, this would be equivalent to approximately 40.6 million lire in 2002 or about €21.42 million in 2025.

Torino’s Role in Italian Cinema

Torino was home to Italy’s first major film studios, including Ambrosio Film (1908) and Itala Film (1909), establishing the city as the country’s first cinematic hub. It produced some of Italy’s earliest and most influential silent films, such as Cabiria (1914), which introduced groundbreaking cinematic techniques. While Rome’s Cinecittà later became Italy’s primary film center, Torino remained important for documentary filmmaking and independent cinema. Today, it hosts the Torino Film Festival, one of Italy’s most renowned events for experimental and independent films.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Torino became a major production center for Rai (Italy’s national broadcaster), which still operates studios in the city. It was also a key hub for commercials, industrial films, and television dramas. The city continues to play a role in Italian TV production, with many series and documentaries filmed in its historic streets and modern studios.

The city’s long-standing film history also played a role in its selection as the host city for Eurovision 2022, following Måneskin’s victory in 2021. While Italy has hosted Eurovision multiple times, Torino’s profound cinematic and cultural legacy made it an ideal choice, further cementing its place in media history.

Torino’s Cinema Museum

The decision to transform the Mole Antonelliana into the National Cinema Museum in 2000 reinforced Torino’s historic role in Italian filmmaking. The museum isn’t just a collection of artifacts; it’s an immersive experience that brings the evolution of cinema to life through interactive installations, historical exhibits, and an engaging layout that sets it apart from conventional museums.

The museum’s exhibitions, spread across multiple floors, guide visitors through the history of cinema. They start with early optical devices, such as magic lanterns and shadow theaters, before moving on to the birth of film in the late 19th century. Original projectors and early cameras demonstrate the technological advancements that paved the way for modern cinema.

The museum also houses an impressive selection of props and memorabilia from classic films, making it a dream for cinephiles. Have you ever wanted to see the original Darth Vader helmet up close? Or perhaps you’re curious about the typewriter Federico Fellini used to draft his scripts? The collection includes legendary items such as the red shoes from The Red Shoes, iconic costumes from classic Italian films, and even vintage movie posters from Hollywood’s golden age.

One of its most distinctive features is its immersive design, where entire rooms are dedicated to different genres and storytelling techniques. Step into a silent film set, where black-and-white aesthetics and exaggerated expressions transport you to the 1920s. Explore the science fiction exhibit, where original props from 2001: A Space Odyssey and Blade Runner create an atmosphere of futuristic nostalgia. Fans of animation can admire early sketches from Italian maestro Bruno Bozzetto, while horror buffs will find eerie artifacts from classic giallo films.

Unlike traditional museums where exhibits are confined to glass cases, the National Cinema Museum incorporates interactive displays. Visitors can explore the mechanics of film projection, experiment with early animation techniques, and even sit in recreated vintage cinemas that screen classic films. A highlight is the giant reclining seats in the central atrium, allowing guests to lie back and watch movie clips projected onto the massive dome overhead—a truly unique experience inside the towering Mole Antonelliana.

Beyond its permanent collection, the museum regularly hosts temporary exhibitions, retrospectives, and film screenings, ensuring that there’s always something new to discover. Past exhibitions have featured Sergio Leone’s original set pieces, a tribute to Alfred Hitchcock’s suspenseful genius, and a deep dive into the costumes of Audrey Hepburn’s most iconic roles. Whether you’re an old-school film enthusiast or a casual moviegoer, the National Cinema Museum blends history, nostalgia, and innovation, making it an unmissable stop in Torino’s cultural scene.

And if you’ve never been a fan of European cinema, don’t be surprised if you leave here browsing Netflix for a taste of La Dolce Vita in your own Cinema Paradiso.

The Panoramic Elevator & Views

One of the most unforgettable parts of visiting the Mole Antonelliana is the glass elevator ride to the top. Unlike most observation decks, this one takes you on a vertical journey inside the atrium, giving you a breathtaking view of the museum before reaching the panoramic terrace beneath the spire.

The panoramic terrace, located at 85 meters (279 ft), offers a 360-degree view of Turin. From here, the entire city unfolds beneath you: the Po River winds through the landscape, historic palaces and Baroque churches dot the skyline, and on clear days, the Alps create a stunning natural backdrop. To the east, the Superga Basilica stands atop the hill, dramatically contrasting the city’s urban grid. Looking west, you can spot the modern towers reshaping Torino’s skyline, such as the Intesa Sanpaolo Tower and the Regione Piemonte Tower.

The best time to visit is sunset, when the city is bathed in golden light, and the transition from day to night creates a breathtaking atmosphere. As darkness falls, Turins’s streets glow with the soft light of historic lampposts, and the Mole itself illuminates in different colors on special occasions, adding to the magic of the experience.

Architectural Design & Engineering

Contrary to what the tower’s exterior may suggest, the building’s interior is surprisingly airy. Antonelli designed the space to be as open as possible, emphasizing verticality while maintaining a sense of lightness despite the structure’s massive scale.

At 167.5 meters (549.5 ft), the Mole Antonelliana was the tallest masonry building in the world at the time of its completion in 1889. It held this record until the 20th century, when modern skyscrapers made of steel and reinforced concrete surpassed it. While still one of Turin’s tallest structures, it now stands alongside contemporary high-rises such as the Intesa Sanpaolo Tower (166 m / 545 ft) and Regione Piemonte Tower (205 m / 673 ft), which use completely different engineering techniques. Unlike these modern buildings, the Mole’s height was achieved entirely with brick and stone, making its endurance even more remarkable.

Originally, no elevator was planned, as the technology was still in its infancy in the late 19th century. However, to make the panoramic terrace more accessible, a hydraulic lift was installed in 1961 in preparation for the centennial anniversary of Italian unification. This system was later replaced by today’s glass elevator, introduced in 1999, which ascends 85 meters (279 ft) through the hollow dome, offering visitors an incredible perspective of the building’s interior before reaching the observation deck.

Antonelli’s architectural vision was anything but conventional. The Mole Antonelliana blends neoclassical symmetry with eclectic experimentation, creating an entirely unique silhouette. The elongated dome and towering spire defy typical 19th-century proportions, making the structure more of an engineering statement than a traditional neoclassical building. Antonelli, known for pushing structural limits, frequently modified the design even as construction progressed, making the Mole an evolving project rather than a fixed blueprint.

One of the most daring aspects of the Mole’s design is its enormous dome, which supports a spire reaching skyward. The original structure was made entirely of masonry, an unusual choice for such height, which made the building vulnerable to weather damage. The spire was reinforced with iron and steel in later years to ensure stability, especially after a 1953 storm knocked down a 47-meter (154 ft) section of the pinnacle. The restoration, completed in 1960, replaced the damaged upper structure with a metal framework coated in stone, ensuring that Antonelli’s vision remained intact while strengthening the building against future disasters.

How to Visit Mole Antonelliana: Practical Information

- Address: Via Montebello, 20, 10124 Turin, Italy.

- Neighborhood: Located in the Centro district, the Mole Antonelliana is centrally situated, making it easily accessible from various parts of the city.

- Accessibility: The museum is fully accessible to visitors with disabilities. However, access to the panoramic terrace requires using the elevator.

Public Transportation

- Tram Lines: Lines 13, 15, and 16 stop near the Mole Antonelliana. For tram 16, disembark at the Palazzo Nuovo or Corso San Maurizio stops.

- Bus Lines: Buses 55, 56, 61, and 68 have stops in the vicinity.

Opening Hours

- Museum: Open daily (except Tuesdays) from 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM. On Fridays and Saturdays, extended hours until 8:00 PM.

- Panoramic Lift: Operates Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, and public holidays from 9:00 AM to 7:00 PM (last ticket sold at 6:00 PM). Closed on Tuesdays.

How much does visiting Molle Antonelliana Cost?

- Museum Admission: €15.00 per person.

- Panoramic Lift: €9.00 per person.

- Combined Ticket (Museum + Panoramic Lift): €20.00 per person.

- Reduced Rates: Available for visitors aged 6 to 26, Torino+Piemonte Card holders, and Abbonamento Musei Piemonte Valle d’Aosta holders. Children under 6 enjoy free admission.

- Book tickets: You can find discounted tickets here.

Contact Information

- Official Website: For more information and online ticket purchases, visit the National Museum of Cinema’s official website.

- Phone: +39 011 813 8560-561.

- Email: [email protected].

Tips for visiting Mole Antonelliana

- Buy Tickets in Advance: To avoid long queues, especially for the panoramic lift, it’s advisable to pre-purchase tickets online through the official website.

- Best Time to Visit: Mornings tend to be less crowded, while late afternoons offer spectacular sunset views from the panoramic terrace.

- Use the Combined Ticket: If you’re planning to visit both the museum and the panoramic lift, purchasing the combined ticket can save money compared to buying separate admissions.

- Expect a Wait for the Elevator: Even with a ticket, expect a wait time for the glass elevator, especially during weekends and peak tourist seasons.

- Accessibility: Priority access is granted to visitors with disabilities and their accompanying persons when picking up tickets at the ticket office.

- Guided Tours & Group Visits: Reservations are required for guided tours and groups, so book in advance if you want a more in-depth experience.

- Weather Considerations: The panoramic terrace is best enjoyed on clear days, as fog or rain can obscure the view of the Alps and the cityscape.

- Photography Tips: Bring a camera or smartphone with a wide-angle lens to capture the breathtaking views from the top.

- Check for Special Events: The museum frequently hosts temporary exhibitions, film screenings, and cultural events—check the schedule before your visit to catch something unique.

- Avoid Peak Times: Weekends and holidays can get extremely busy. Visiting on a weekday morning ensures a more relaxed experience.

- Best views of the Tower: The one downside of visiting the Mole Antonelliana is that you don’t get to see its unmistakable silhouette piercing the Turin sky. For the most breathtaking views of Turin that include the Mole, head to Monte dei Cappuccini, a hilltop vantage point offering a postcard-perfect panorama of the city, especially at sunrise or sunset. Alternatively, for another striking viewpoint, visit the Villa della Regina, where you can admire the Mole framed by the city’s historic rooftops with the Alps in the distance.

Final Thoughts & Is It Worth Visiting?

The Mole Antonelliana is more than just a building—it’s a journey through Turin’s past, an architectural experiment, and a gateway to the magic of cinema. Whether you’re an architecture fan, a film enthusiast, or just someone looking for the best view in the city, this is a place that delivers.

If you’re visiting Turin, the Mole Antonelliana isn’t just a recommendation—it’s a must.

Leave a Reply

View Comments